We are occasionally asked why fine art is so expensive. People have asked, for example,“How much does a piece of canvas and a tube of paint cost? It can’t be more than a few dollars for the materials.” There is more to it than materials, however, and I can think of three things. First, running a small business involves overhead; second, making an oil painting requires specialized skill; third, the final product is unique. In parts one and two, I discussed overhead and skill, this article is about the third idea, unique products.

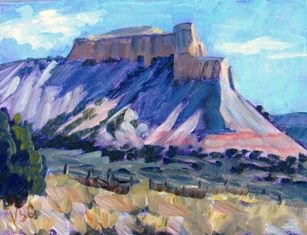

We are occasionally asked why fine art is so expensive. People have asked, for example,“How much does a piece of canvas and a tube of paint cost? It can’t be more than a few dollars for the materials.” There is more to it than materials, however, and I can think of three things. First, running a small business involves overhead; second, making an oil painting requires specialized skill; third, the final product is unique. In parts one and two, I discussed overhead and skill, this article is about the third idea, unique products.In May of 2008, Christie’s sold a Thomas Moran painting called Green River of Wyoming at auction for almost 18 million dollars. Eighteen million! For a Thomas Moran! During a recession! Why can a painting like that command such a price? Because there will never be another one. It is the only one in the world, a one-of-a-kind beauty, painted by a man who died in 1926. I’d really like to have that painting myself, but so would everyone else, and someone is willing to pay more than I could ever afford.

What about paying that kind of price for the work of a living painter? Can’t we expect that they will produce many more similar pieces? Yes and no. It is true, of course, that living painters generally command less for their work because fresh paintings by them are neither rare nor unexpected. It is not true, however, that any painter will paint forever, and, if you see something from their easel that shows them clearly at the top of their game, you can count on owning an exceedingly rare and unique object.

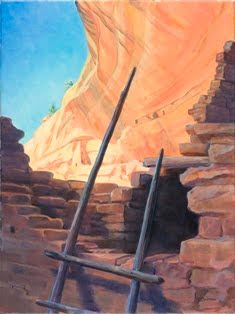

In our experience, it can often be worthwhile for an artist to create pre-painting studies or post-painting copies of an outstanding scene. We have done that in some cases, such that there are two or three works with very similar subject matter that have been sold separately. I suppose that each study or copy that is sold can slightly diminish the value of the original full-sized work, but the thing to keep in mind is that even the study is a hand-made item. The study is not a photocopy, is not a scan, is not mass-production duplicate. It is, instead, a hand-made object with all that implies. It has unique brushwork, paint choices, and even mistakes. In short, it remains a one of a kind piece of art.

Prints, on the other hand, are not made by hand. Prints are prints. Whether they are called giclees, limited edition prints, or posters, they are all machine-made. They are imaged, scanned, or machine-copied and are available for mass-production. As a result, they should be priced accordingly. They may be perfectly nice objects, but they are not unique. In our business, we have done a small amount of imaging and have attempted some giclees. We have not, however, generally been happy with the quality of the product and have sold very few of them. In any case, they are not expensive and will never command the price of an original.

I sometimes joke with art buyers that the painting they are buying from Valerie will become much more valuable tomorrow if Valerie is hit by a truck today. Not very funny, really, but it illustrates my point. Fine art is expensive because it is unique. It is a one-of-a-kind, hand-made object. There will never be another one like it. And, in about a hundred years, if you hang on to one of Valerie's peices, it might even be worth $18 million.